The whole world was a dim and textured red from the cloth thrown over her head, pinned in place by heavy jewellery laid over it. Big circles of bronze and gold rested over the caps of her collarbone, balanced on the cols of her shoulders, droplets, swings, and chains draped down her back, but she couldn’t feel any of it except as weight.

The tent was warm but her skin was cold. Absolute stillness kept her from being stifled, but her back was tired. A little slide of her backside off of one heel or the other reminded her she had limbs and held momentary relief, but shifted the heavy jewellery, earrings brushing at her cheeks – a light tinkling of tinny metal from the wedding crown what felt like a foot above her head, its weight resting securely in her pinned and braided hair.

None of the metal touched her skin. It would tomorrow, in theory, when she was re-adorned to emerge as wife, if that was how things were going to go.

Outside they were chanting – or singing. She put red-dyed fingers to her temple to clear distraction, causing a cascade of drapery and ill-defined adornment.

In Geron they called the hours of prayers, loud, ululating, despairing and joyous, but they did not do that in Ainjir. Maybe, she thought, that was why their neighbours had hated them so, but such thought was only a joke; in Geron the Midraeic villages were shadow-settlements, out of sight, much less hearing, of their Geronese neighbours. On feast days – like weddings – the Ainjir Midraeic called the hours, but what was outside her wedding-tent was mostly singing.

She could hardly see the colour on her own hand as she held it out before her, but knew it had come out of the dye a kind of pomegranate-stain red. Singularly unimpressive. It would maybe become purpleish, after some time, but right now it was just a blurry match to the fabric over her face.

She let her hand come to rest on her thigh again. She didn’t know the woman who dipped her limbs in perfumed dye, and this angered her. Just one of many improper things about this whole ridiculous ceremony.

There was no courtship, though she imagined they must have asked her parents for their approval, and, of course, she had agreed, and he must have agreed.

There was no exchange of favours between the families. No negotiation of the elders. No long, smoke-filled, crust-strewn night of barter over abandoned pots of tea that grew cold too fast and sticky-rimmed glasses of whatever-derived caecuban chosen by old men. Then again, there were not that many old many to choose on her side of the family.

There was no feast of sweets, parade of gifts – she and the strangers who dyed her skin and combed, braided and arranged her hair had sat mostly silently, eating sticky balls of dough. They tasted like paper shellacked in over-hardened honey and she made herself eat them because God knew she was going to need whatever charm they imparted no matter how this came out.

Everything tasted bad. Outside was the feast, and she was sure she had eaten some because she would need her strength, but only remembered sawdust in her mouth. They had grasped the rope – her and her soon-to-be husband, and done the steps around the fire, and it had stayed fast and strong and only blackened a little, but that was probably because it was a weak, shitty fire.

Perhaps Gaius didn’t want to risk any bad omens.

She and her betrothed had turned away from one another ceremonially after the dance, but then they had each acted like they were already in their own wedding tents until the ceremony ended.

She had dropped the plate staring directly into his eyes. If there had been anything in there, she had not seen it.

The stupid plate shattered catastrophically, exactly as it was supposed to – even bad enough that the women attending her – strangers, all strangers – had bent to carefully sweep the fragments away out of fear for the couple’s bare feet as the ceremony proceeded.

Fuck his bare feet. They should be thinking only about her bare feet. If they were not strangers they would be.

She had rested her hands on a stranger’s shoulders while another stranger lifted the hem of her skirt and put one delicate, useless wedding shoe on at a time before they left that one of the endless series of ceremonies to pop back into the feast for a minute or two before the next extremely grave ceremony began.

All of it was ridiculous.

Not because of the ceremonies, which held deep meaning even when they were ridiculous, but because all of it was done to better secure the match when the whole edifice could have been challenged and the match revoked for any of a hundred violations of the development of a proper contract for a Midraeic marriage. So there was tiresome chanting, and elaborate bedecking, and extra-thorough ritualistic pacing behind very proper shades, and none of it really meant anything because it could all be invalidated at a word.

A word she wouldn’t say.

Her brother wouldn’t say.

Her father and mother weren’t here. These jewels weren’t her mother’s jewels – not even her Ainjir mother’s. Whatever had been her mother’s lay mouldering in the ground somewhere between Ainjir and Geron if such a shallow grave had kept them from being scattered across the cold earth, or, she had to admit was far more likely, adorned some Geronese daughter on not particularly special days. Or had been melted down into a nice set of candlesticks or good serving plate.

Her Ainjir mother’s jewels would have been different – they were dancers, the Ainjir Midraeic, and made jewels for dancing – but she would never see them. Maybe none of them would ever see them again. The family was not rich – too big to be rich across cousins and brothers’ wives – and the coin the jewellery represented not substantial, coming as they did mostly out of the bride’s side, cobbled together of bits and pieces of broken everyday pieces.

Perspica was a woman of forethought but also not sentimental and Catillia didn’t even know if she would have packed them when her son said it was time to flee. Not if it meant leaving behind something useful, like a knife, or cheese.

Catillia thought it strange that of all the things she knew of their preparations to leave, she had not thought of the wedding jewellery. She had not been thinking of weddings at all, and maybe that was foolish. Women were supposed to think of weddings. But then, many things were supposed to have happened.

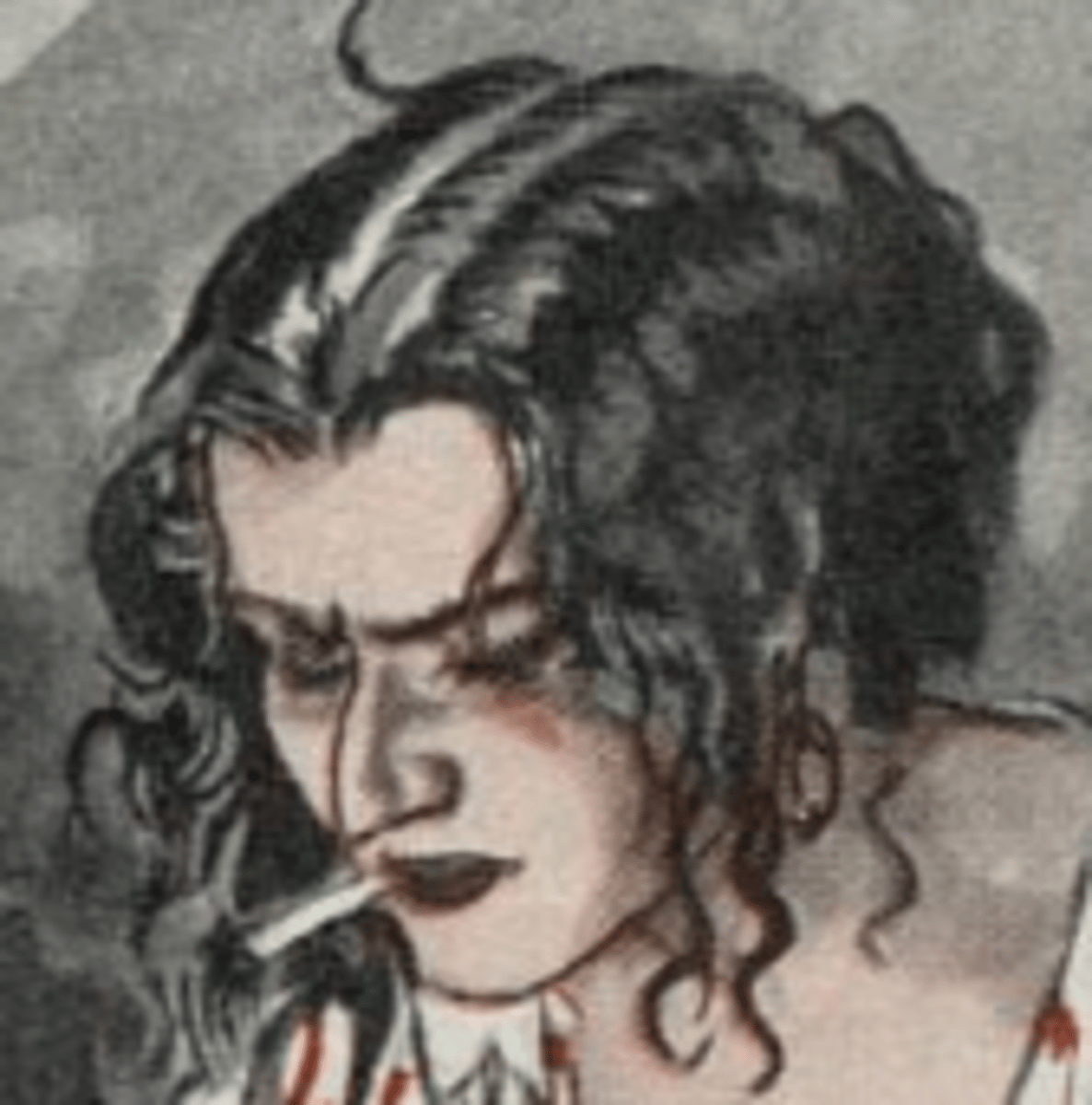

Her sisters were supposed to braid her hair; it should have been Iona mixing the dye and perfume and dying her skin; the village girls picking and draping the scarves and setting the wedding crown and placing the heavy necklaces and bracelets and rings and earrings – painting her lips, arranging her tent, chattering and snacking and passing licentious rumours while the older women tutted at them. It should have been an old woman she knew showing her the simpler knots for her taenia so her (presumably – unlikely) ignorant husband could figure out how to undo them.

But it could not be anyone else here. She doubted her sisters would have imagined her insisting, when Gaius came calling, but even they sometimes misunderstood her. And it had taken insistence; she was almost too old, her behaviour too odd, her relation too distant, but she had insisted. They had insisted. And shock had been overcome by grief, but there had been shock.

Too often one mistook independence for hostility but Catillia had imagined weddings.

The oil dish sat on the small table before her and blazed. She couldn’t see the figures pressed into it, but caught glimpses around the flame. This should have been given to her, into her hands, by her betrothed, so she knew exactly what it looked like, and should not have just appeared in her wedding tent, put there by someone she didn’t know. She had always thought this most romantic, the very most if it were made by her own husband’s hand instead of bought, but then that would mean marrying a silversmith or some other fine metalworker and she never knew any.

Maybe that was why she didn’t think of weddings. Had she known a silversmith she would have snagged him, quick.

Well, only if he was any good.

This wasn’t a very efficient dish, but it didn’t have to be.

She could imagine it being set by Spesnova – Spesnova would have the most fascination, be the most interested in the fine gift of future husband to future wife, and most interested in the role it played and the meaning it gave the wedding night. Spesnova had the most imagination.

Spesnova was also just old enough, and most beautiful and sweet, and undoubtedly who Gaius would have preferred.

Spesnova was too delicate. She had been the child of hope. They coddled her, perhaps too much. She was not one to wilt – she could hardly have survived this family had she been. She would be strong enough when called on, but they all hoped to never see her called.

Certainly not to this fate.

Auriol – well, Auriol would have brought a knife. She would have murdered her husband and then herself. Barring a knife she would just beat him to death with the wedding jewellery and swallowed a coal. Not a second thought given.

Too often one mistook quiet for compliant.

They probably thought Catillia would bring a knife and stab her husband to death, at least. She had thought about it. Maybe she would, eventually, depending on the nature of the oncoming horrors. But she didn’t particularly want to die, and killing her husband on their wedding night rather voided the contract. They would just make a new one, probably.

Naturally, satisfying as vengeance might be, Auriol couldn’t die, Spesnova would not be subjected to this, and the others were too young, so here Catillia was, having shocked the pants off everyone – except perhaps Dominicus – by agreeing at once. Pushing for it to be her. Having argued to put herself in such a position.

Whatever his hesitation about Catillia, and his many hesitations about Dominicus, Gaius had believed them and the plans had gone ahead.

Whatever her steadfastness then, now in the wedding tent, Catillia was thinking about the earlier decision not to bring a knife, regretting it a little.

Gaius’ women surely would have searched and maybe found it, anyway. A bride-to-be spent a lot of time naked, so where exactly could she hide it? Nobody would sneak it to her, as she knew none of these people. Again, Gaius wasn’t stupid (most unfortunate) and that was why she knew no one, nothing in this tent was familiar, and not more than ceremonial words had passed between her and her betrothed. She couldn’t even remember what his face looked like, having gazed into it only hours before; she was hearing the cries in the town square in Geron and wondering what her mothers’ jewellery would have been like.

More pressing matters called her. Gaius wasn’t stupid, but she couldn’t exactly fathom what it was he thought marriage of Dominicus’ sister to his son would accomplish, however, and that made her uncomfortable.

Surely he must have realized that Dominicus could not be controlled by so loose a tie as a forced marriage? Wills of the parties involved being against it, the families unconsulted, the contract could not stand. Sure Gaius could especially not imagine it of a forced marriage to Catillia, who for all his occasional faults Dominicus understood to be able to take care of herself–

But how sure could she be? What was known and was unknown by a man who seemed to have known what they would do before they had decided to do it? Against such a man they could not rationalize, could not plan – only guess, only react.

Perhaps there was something wrong with his son, and this was a convenient way to add an element of management to his unruly Grand Dux and to his offspring, but this again befuddled her. As a newly-wedded couple, they would have time apart from it all–

Time apart from it all was keenly denied Dominicus and their family – what control could Gaius exert from a distance? Was his son so servile he could be expected to act in accord with Gaius wishes even at a distance? What benefit did Gaius gain by attaching Catillia to his son and losing them to a honeymoon?

She vaguely knew the son was involved in Comid High Command, as he could hardly not be, as Gaius’ son, but that was all. Perhaps threatening Catillia would be his way of managing them both.

But it did not sit well with her an answer: too many unknowns.

True: Gaius did not know Catillia directly, though he would have learned as much as he could.

Equally true: Gaius may not have known Dominicus, but he had an uncanny understanding of how to control him.

They had been outmanoeuvred by Gaius critically, more than once, and this was not a feat easily achieved; she refused to be dazzled by it but it was confounding, and she knew it had deeply unsettled her brother.

Dominicus had seemed surprised and not surprised when they first met after the betrothal had been made. Her little brother had lost weight, and put on stringy muscle. She had thought him half-wasted when first they had been caught by the Comids, but he apparently had more to lose. He had grown hard, and tired, shadowed in their months apart and still he looked at her like her little bubble, the sweet usurper child, her best and beloved little scholar. He was still in there, but hiding deep.

Of course they knew she was the only choice, but they could both still regret it.

And that was why none of her family were here. Gaius knew it put the ceremony on shaky ground, but to let Dominicus have any idea of where his family was would be the last mistake of his life. Whatever loyalty Gaius thought he gained, however much blood Dominicus spilt to further Gaius’ aims, there was no world in which threatening his family led to anything other a most rapid and brutal death the minute Dominicus thought he could accomplish it.

That made Catillia smile. Gaius truly had plucked a bear’s ears while picking mushrooms, and somewhere back in that winding, plotting mind he knew that he could never let go.

They had even gone so far as to blindfold her leaving the place the family was being held, doing loops through the roads and countryside to try to confuse her sense of direction, so there was not one single solid fact she might convey to her brother. Probably, the whole family had been moved immediately after, as the changed delays in messages back and forth seemed to imply.

So back to the dull waiting. No sense could be made of Gaius’ decision, except that, for whatever his political and strategic sophistication, he still somehow believed the intertwining of families would create an alliance – an attachment, a something. The only other option was that this was some new terror or form of control, and Catillia should have been like Auriol and brought and knife regardless. To be terrified would be to waste her energy, and whatever came, she had at least decided how to face it.

At the moment, that was ‘bored’.

The veil barely shifted with her sigh.

Outside, there was a small commotion. A rustling of cloth, growing and dimming of noise, the sound of shifting metals and steps.

She heard the murmured blessing, or whatever it was men did right before entering a bridal tent, before whoever else had come in left and between her and her husband was one last drapery.

Horror, or...?

He stepped inside.

Men, too, had ceremonial clothes, jewellery, a big stupid jewelled bag and dagger – it wasn’t a real dagger, not at all sharp – and all of it was meant to make him look good, turn whatever shape the man was in into the shape of a man. It was decently effective. He had no dumb veil to look through, though.

Yet, for all he was a blurry, red-cast, man-shaped thing, she must be a squat, unreadable, conical thing. With a nice hat.

She didn’t move, and he didn’t move.

Finally, he approached the cushion opposite her and the oil dish and knelt.

“My name is Mettius,” he said, his voice deep, clear and almost clipped, but not imposing.

This was awkward. They had both been walked through the ritual parts of things, but he wasn’t starting it right, and naturally that ritual had one end. She wasn’t supposed to speak except in certain replies, and anyway, he certainly knew her name.

“Do you want to see?” he asked. He cleared his throat and much closer to a mutter added, “I would want to see.”

Saying the words started the ceremony, so if he was not saying the words, she was not saying the words. She tipped her head slightly in assent, hearing the little tinkle of the metal on the bridal crown.

Clearing his throat again, he put his hands out slowly, then inched his knees forward so he could actually reach. Exceedingly gently, as if she might cascade into nothing like a pile of sand, he lifted away the wedding crown. Setting it delicately on the ground – more on her side than his – he tugged loose the veil rather than lifting the jewellery off, his delicacy making this process last long, awkward minutes – if she were flatbread she would have burned to black coal before he risked enough heat on his fingers to flip her.

Lifting the veil off, he suddenly became bashful – or something – as he carefully folded the material and put it aside on top of – no, better to put it beside the crown.

She couldn’t decide if the clearing of the throat was a nervous tick or an actual disease. Still, he said nothing.

“Catillia,” she said, making him startle.

He was extremely hesitant to meet her eyes, so she had all the time in the world to stare. There was nothing remarkable about this man – if he were some kind of monster, it was not evident. He was a little round-cheeked. He had little moustache, but should grow a beard. Not unhandsome turn to his nose, a jaw that would be stronger if he were looking up. Big, manly eyebrows. And now that she could see in fine enough detail, the clothes appeared loose rather than holding him desperately in shape, like maybe he was a little scrawny.

A normal-looking Midraeic man. A little Gaius in his features, but that couldn’t be held against him. She wondered what his mother looked like. Maybe she was distinctly featured, but Catillia imagined her as round, mostly.

He was sweating.

Well, it was warm in the tent.

“If it were me,” he said abruptly, making the effort to look at her face, “I would have brought a knife.”

Catillia smiled but his eyes had already roved away. “I don’t want to be stabbed. I am not a fool; I know we have made an agreement that may not be to our own wishes. I have no desire to impose beyond what has been asked of me, which was to marry you, which we have done. We may begin negotiation from there.”

A thousand things occurred to her to say, but she went with:

“Why should I not expect you to have a knife?”

He pulled back in shock. “What horrors do you expect of me?”

“Your father has kidnapped my family and wars with the whole country on a holy crusade that they mostly don’t want.”

“That is bad, yes,” Mettius said defensively, “but your brother organizes great and ferocious battles, the likes of which the nation has hardly seen and has personally killed people.”

“Are you not a soldier? He is Grand Dux,” Catillia said. “That’s his job.”

“I am... not a very good soldier. I help with dispatches – write things. More a messenger. Grand Dux Galen scares me,” Mettius said, his expression so full of guileless concern she believed him immediately. He said it as if to his left knee, but continued trying to address her. “I do not wish to come to his attention as a threat.”

“That’s reasonable,” she said, another phrase which took him aback. “I’m afraid you already have, though.”

“But, if you can see it as other cowardice,” Mettius said, some hope in his voice, “I would rather have not been involved at all. I don’t want to make a further fuss.”

“I dare say we did as well, my family, but we had little choice. Why in the world did you agree to marry, then?” she asked, torn between maintaining her wariness and an encroaching, deep amusement.

“My choices are... less but still limited. And I agreed for the same reason you would, I imagine,” he said. “It was my duty.”

She laughed, and he again pulled back, this time with shock and confusion.

“Your duty to your father outweighs your duty to God?” she asked.

“What?” he stammered. “Duty falls first to one’s family – duty of the offspring to the parent is sacred, as it partakes in vocation, like the call to prophecy. In what way do I mislay my duty to God if I am obedient to my father?”

“Surely it is of greater concern to God that you profane his ceremonies with insincerity than that you obey your father. Many fathers were disobeyed in the Books, but ceremonies were laid down, step by step. And also there is the nature of vocation, divine vocation, and procreation, in which duty may be seen as a river and a mill or as a tide which both waxes and wanes.”

“But these are all interpretations,” Mettius said, “and interpretations may be different between the People – duty remains among the highest callings, and its role between child and parent among the clearest.”

“Eha!” Catillia chirped, holding up a finger. “Sincerity is of far greater weight than either duty or interpretation as it appeals to the state of life as it is lived and felt in the time given us by God – this is a basic theological principle.”

“I am not particularly good at theology,” Mettius said with the slightly petulant weariness of an oft-scolded student. “I mostly follow the advice of my father.”

“Your father is a lunatic,” Catillia said.

Instead of slapping her, shushing her, demanding repentance, insulting her back – Mettius winced. “This is perhaps not the wisest conversation to have, and besides, I have not the expertise to judge in the matter.”

“Wisdom flees before this undertaking! What are you even doing here!” she demanded, jewellery clattering as she threw out her hands.

“I hoped for a longer conversation in which we might both come to terms acceptable to the other, but I must explain to you now that we are wed that I am a disappointment to my father. Though I hope to do better in our marriage, I feel it unfair to welcome you to our house without explaining that my father sees little to hope for in me, though I am trying to do better.”

This had the air of a prepared speech, and Catillia’s jaw did not fall open, but did fail to rise up and close her mouth.

“Whatever ambitions of a high household you may have held must be tempered by understanding my status, and our happiness will be facilitated by eliminating expectations of particular regard. While I believe I can promise a sufficient household, suitably well-appointed, I have found it best to avoid rather than court special attention in accordance with a higher station. This track I would advise we continue in our married life, particularly in our relations with my father’s household. My mother, my father’s first wife, may the Prophet hold her hand in the afterlife, was not the favoured wife...”

“Your father has multiple wives?”

This interruption derailed him. “I... yes,” his eyes widened, seeing her expression, “I don’t want multiple wives. I didn’t want one wife.”

She turned her head to look at them with the side of her eye and his stammering worsened.

“I am not unpleased to have a wife! That’s not what I meant! I am not a suitable husband, being a disappointment, and I can’t foresee satisfactorily providing for a wife when I’m not a good son!”

“Who says you are not a good son?”

“My late mother, God watch over her, was more gentle, but my father and his other wives–”

“They have all told you this nonsense?”

“It cannot be nonsense when it is reflection of those highest authorities on earth–”

“Bah!” Her jewellery jingled.

“I don’t–”

“The Prophet is the highest authority on earth, and thus the books mediated by scholars of his teachings.”

“According to Laimon, the Prophet’s ascent–”

“That He is dead is no matter.”

“I... ‘dead’ isn’t... I think that’s heresy.”

“Heresy if you are going off the statements of an idiot like Laimon.”

Mettius hesitated, then raised a finger to venture: “Though supplemented by other texts, Laimon’s Arguments are foundational to the Comid Republic’s philosophy.”

“I will not tell you what I think of the Comid Republic’s philosophy, or we shall have more debates about the wiseness of certain conversations.”

Mettius fell silent, and Catillia waited, bedecked fists on her hips. His eyes roamed the carpets, the dishes, the tent walls, the pillows and every candlestick.

“Do you want to finish your speech?” she asked.

“Yes, please.”

She gestured for him to continue.

“I... well, I suppose I may draw to the point instead of continuing exactly. I have no special skill in learning. I have no great skill in combat as your brother has, and no great strategic mind as my father has. My fathers’ other wives resent their inability to produce another more satisfactory son and are unlikely to receive you favourably, due to my own failings rather than any you might have, so I would suggest we avoid them. I suspect that my father has made this offer marriage to unburden himself of my direct maintenance and for whatever other benefits I cannot determine. I think I am perhaps a liability. Likewise, I have agreed out of duty but also to secure an escape for myself from duties laid upon me which my performance thereof only disappoints him. I have entered into this marriage selfishly, and regret the disadvantage which has required your acquiescence to it. By presenting this to you I mean to convey that I hope to be a better husband than I have been a son.”

He gave her a nervous nod, something like a bow in which he was unwilling both to look away or look directly at her. Catillia indulged in silent thought for a moment, watching the flames move around in the oil of their shallow silver wedding dish.

Finally, she said, “I didn’t bring a knife.”

“Oh?” He visibly relaxed, though still quite tense.

“I still wonder if you are saying all this to secure some kind of advantage or undue cooperation,” she mused aloud.

He winced again. “This was something I considered, but I am neither very good at deception nor very strategic. Acquaintance, I felt, would surely prove it to you, so it was best not to delay. Also I did not want to be...”

“...be stabbed,” she finished with him.

“By you or later by your brother, if at all possible,” he added.

“Logical,” she said.

Catillia cut him off before he could speak: “Don’t tell me you’re not very good at logic.”

They sat in silence while she thought again.

She believed him, not because of seeming sincerity or disbelief in his ability to deceive, but because it provided an answer to an important question – one she would not get the chance to share with Dominicus, but which gave her great hope all the same.

She had barely seen her brother in the lead-up to the wedding, and he was given no role in the ceremony itself despite being her only relation present. This was Gaius’ decision, because it would torment Dominicus, what he had done in marrying his sister off, though it was the only choice both she and he could make. Such little torments divided Dominicus’ attention and kept him from focusing on Gaius. Now Dominicus could not save them all, because Catillia would be with her husband and the rest of the family would be wherever Gaius kept them, so if Dominicus would not give up on the idea of saving his family – and he would not – his plan would have to become more consuming, more complicated, more difficult to imagine.

A tiny gain for the steep cost of an eldest son.

Gaius had not plucked a bear’s ears picking mushrooms, he had thrown his bolas at a bird over a lake. God, she hoped Dominicus would understand – she had no means of telling him, he had no greater chance of knowing, so she flung the prayer upward.

Because now she knew why Gaius had so strongly pursued her brother in the first place, and that Gaius not only made mistakes, but made grave ones.

But for now, they both simply had to last until they could communicate again.

“Eha! Well,” she said, shaking out her hands and flapping her elbows to get airflow going under her stifling layers of scarves, “let us at least complete this part of the ceremony, and we can continue our discussion in comfort.”

“Do you want me to...?” he gestured at her clothing and she nodded.

“We should at least do this part right,” she said.

He nodded, and began to lift away the heavy jewellery, the start of the long process of ceremonial removal of the clothing that would place them again at the very beginning of humanity, the innocent and naked confrontation of man and woman.

She wondered what he would do then? She sincerely doubted that he had even thought about it – no strategist, after all – as this was, after all, just the next of what had been a long, winding set of ritual steps.

Perhaps it was fitting, this most overblown of the ceremonial metaphors, after all.

“Oh!” he said, pulling back, looking up into her face, eyes meeting eyes in sincere solemnity, “I also do not have a knife.”

She smiled, arms raised to let him continue undressing. “Next you will say that you aren’t sure the Comid Republic was worth plunging the country into civil war.”

Mettius frowned slightly, absorbed in the task of unwinding the scarves like the puzzle of them pleased him, and he had thought little about the fact that he was next. “The plate shatters at a wedding because all that is joyful is tinged with sorrow; some say it is the death of the Prophet, but Laimon argues the tempering of joy, the shattering of the plate, is because Comidras fell and like fragments the people of the Prophet were scattered, never to assemble again with such corrupt pride before God.”

He wasn’t looking, but Catillia smiled again.

“Maybe Laimon is not always an idiot.”